What is JavaScript

JavaScript is a programming language that powers the web. It allows you to dynamically update content (like displaying how many times a button is clicked), enable user interactivity, and is the only reason websites can respond to input instead of being static pages.

I cannot teach you JavaScript in this session, it would take a tutorial longer than the whole of this one. But I can provide you with the basic tools you need to use it within Roll20.

We won’t learn all of JavaScript, but we will cover variables and functions, as well as the most common uses you’ll have for this language inside your Roll20 Character sheet.

By the end of this session, you won’t be a an expert in web development or JavaScript, but you will be able to respond to players’ clicks, changing data, and dice rolls. Let’s begin!

Console.log

Console.log is the single most important tool for using JavaScript.

Whenever anything happens in your code (like an error!), it gets logged to the console. But you can open up the console yourself. And more importantly, you can log your own data there, error or not!

This is a great way to see what your code is actually doing, validate that your listener was activated, or confirm what the value of a variable is.

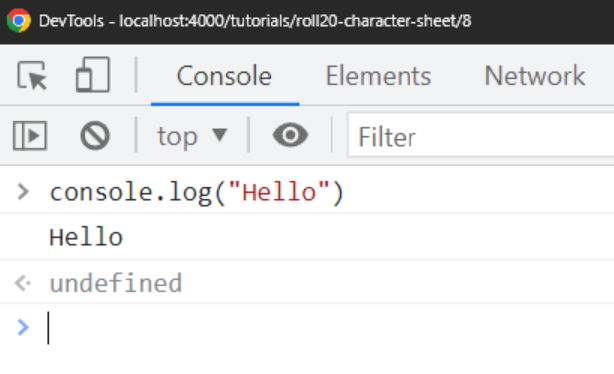

To use console.log, there are two steps. First, you have to call console.log() from within your code, with the data you want to log. For example, console.log("Hello")j would print the word “Hello” to your console.

Second, you have to open up the console to see it. If you’ve been using the Element Inspector (and you should be!), most browsers show the console on the same window, as a different tab you can click on.

You can launch the console by hitting f12 or ctrl + shift + j on most browsers.

Tip: If you’re on a mac, use cmd + shift + j instead.

The neat thing about JavaScript is that your console is also a fully interactive JavaScript playground! Go ahead, open it up and type console.log("Hello") in there now. You should get a “Hello” back!

Don’t worry about the

Don’t worry about the undefined, just focus on the happy Hello

Do you see the same thing? The console will be a critical part of this tutorial, and of using JavaScript, so make sure you have this working before continuing.

Every line of JavaScript (except for

ifstatements and function declarations) should end with a semi-colon (;).

It’s a good idea to leave the console open while you work. Errors will appear here (in red!), and it’s a great way to see what’s actually passed into a function, or to verify that an event is getting hit. Just toss in a console.log and see what’s happening.

Why do my commands keep saying

undefinedin the console?Every command in JavaScript can return a value (more on this later, in the functions section). Most commands don’t return anything meaningful, but the console tries to read their return value and print it anyway. Since there’s nothing there, it helpfully tells you that the return value is undefined.

You’ll notice that while

let x = 5returns undefined, if you subsequently typex = 10, 10 will be returned. Declarations don’t return, while assignments do.

Variables

Variables let you store a value and use it later. A variable can also change, to point at something new.

For example, “the president” is a variable that points to one person. As of my writing this, it points to Joe Biden. Ten years ago, it pointed to Barrack Obama instead. One variable can hold multiple values at different times (but only ever one value at one time).

If you’re thinking “Hey now, I’m not American, ‘the president’ doesn’t refer to Joe Biden, it refers to <some other president>”, then good news! You’ve discovered something called “scope”, where a variable might only be relevant within a certain context.

Ironically, the topic of scope is outside the scope of this tutorial (we will only allude to it).

We declare variables in JavaScript using the let keyword, like this: let x = 5;. This creates a new variable called x and gives it a value of 5.

Variables cannot have spaces or hyphens in their names. They should start with a lowercase letter, and can contain underscores and numbers.

Then I can refer to it later. Go ahead and type these commands into your console and hit enter. Do they do what you expect?

1

2

3

4

5

let x = 5;

let y = x + 1;

x = x + 5;

console.log(x);

console.log(y);

If you’re losing track of what is being printed, there are two ways you can solve it. Either by combining the value with a label (

console.log("x has a value of " + x)), or by logging multiple things with a comma:console.log("x has a value of", x)). These have the same output.

You can declare variables of other types too, the exact same way.

1

2

3

4

5

6

let name = "Alex"; // A string is a collection of characters

console.log("Hello, " + name);

// true and false are key words

let isAuthor = true;

let isPresident = false;

Don’t worry too much about the “type” of a variable. No one but you will be calling your functions, so you can guarantee that no one will give you “Hello” when you’re expecting a number.

But variables can only be defined once. You can change the value of a variable simple by assigning a new value to it (x = 10), but if you try to declare a new variable with the same name, you will get an error.

1

2

3

let x = 5;

x = 6;

let x = 7; // Error! x is already defined

Comments

Just like in HTML and CSS, comments can be useful so you remember why you’re doing something a certain way.

In Javascript, you leave a comment with //

You can also leave a multi-line comment with /*, ending it wherever you feel like with */.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

let x = 1;

// This is a comment

// x = x + 5; // This won't run; it's commented out

let y = 0;

/*

All of this is commented out

y = 50;

Even this!

*/

console.log("X is " + x + ", y is " + y); // X is 1, y is 0

If you are using a text editor like Visual Studio Code or Notepad++ (and you really should be), it will provide syntax highlighting, like the text above, which makes it clear to see what is being commented out. Usually these are styled as light gray or green by default.

Functions

A function is just a sequence of commands that can be run. Most functions return a value.

Functions take in 0 or more parameters, called arguments, and do an operation on those parameters.

Tip: a function is a block of code that takes input, performs some logic or operations, and then returns a single value, usually dependent on that input.

The simplest function we can imagine is one that takes no input and always returns the same value. For example:

1

2

3

function getTheNumber2() {

return 2;

}

or

1

2

3

function getMyNamesAndTitles() {

return "Sir Alexander Rinehart of the Royal Court, Ruler of the One Blog(s) and Tweeter of Tweets";

}

This second function might save me a lot of time, and if my titles ever change, I can just update them in one place!

To call a function, I just use its name followed by parentheses. If I need to pass in any input, they got in the parameters.

1

2

let name = getMyNamesAndTitles();

console.log(name);

Or, if I was commonly making new blogs, I might change the function to look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

function getMyNamesAndTitles(numberOfBlogs) {

const titleStart = "Sir Alexander Rinehart of the Queen's Court, Ruler of the ";

const titleEnd = " Blog(s) and Tweeter of Tweets";

return titleStart + numberOfBlogs + titleEnd; // You can combine strings with +!

}

Then if I start a second blog, I can just update my function to

1

const myNameAndTitle = getMyNamesAndTitles("two"); // Change to "three" if I start another blog.

The

constkeyword is used to define a variable that will NEVER change. You can always uselet, but if you know something shouldn’t be modified, you can useconstinstead. This can save you from accidentally reassigning it later (that would cause an error!)constis basically a signal to yourself and a safeguard.

Most functions take in input and then use that input to determine a result.

For example, I could have a function called Add2 that takes in a number, adds 2 to its value, and then returns it back to the place where it was called.

1

2

3

function add2(num) {

return num + 2;

}

Now that I’ve declared it, I can call it with:

1

add2(5); // returns 7

To actually use the returned result, I probably want to save it in a variable, or to pass it into another function:

1

2

3

let x = 5; // X = 5

let y = add2(x); // X = 5, Y = 7

let z = add2(add2(2)) // z = 6

You’ve already been using one function: console.log() is a function that takes in an argument (the data you want to log), and performs an operation (logging it to the console). It doesn’t return anything though.

You will be using a couple built-in functions (like getAttrs and setAttrs), but you can also write your own!

To define a function, you type the word function followed by a space and the name of the function. This can be almost anything, as long as it doesn’t start with a number.

You can use letters, numbers, and underscores (_) within a function’s name.

After that, put two parentheses (). If you want to take in any arguments (or parameters), name them now, separated by a comma. function myfunc(arg1, arg2). Then, just add curly braces {}, and put the code you want to run in between!

A function can be as long as you want, but the last line of it should always be a return statement with the value to return.

(Slmost) every line of JavaScript should end with a semi-colon (;).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Takes in two strings and returns twice the

// Length of the first string plus three times

// The length of the second.

function getModifiedLength(first, second) {

let firstLen = first.length * 2;

let secondLen = second.length * 3;

return firstLen + secondLen;

}

Tip: If you have a complicated function, like the one above, it’s a good idea to leave comments for yourself about what it does and how it’s used, as well as what it returns. You’ll thank yourself later.

When you’re naming your arguments, there are a few rules. Just like when naming a variable or function name, they cannot start with numbers, but can use underscores, letters, and numbers. Hyphens are not allowed.

Part of the flexibility of a function is that it can be called from multiple places with multiple different values. The parameter that you pass in does not need to match the name of the function’s argument.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Whatever variable or value we pass in,

// We'll refer to it as "str", but only

// Inside this function.

function getStringLength(str) {

return str.length;

}

// The variable we call name will be passed in

// We don't care how the function returns to it.

let name = "Alex Rinehart";

let length = getStringLength(name);

// "str" has no meaning here, outside the function!

A function’s argument. That’s part of the flexibility.

There are some reserved words that cannot be used as variable names, function names, or parameters. These include: number, return, char, double, break, public, in, case, new, and this. You can find a complete list online.

You will write special functions called listeners that listen for a certain event (like a button being clicked, or a value changing).

You may also write helper functions for yourself. For example, Cyberrats has a method that takes in the name of a room as a parameter and returns the text of that room. This is used in the basebuilding part of the character sheet. If a player picks a room’s title from the datalist, the description for that room is automatically filled in.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

function getRoomDetails(room) {

// We'll talk about conditionals next

if (room === Rooms.Armory)

{

return `Unlocks all of the armor and armor tags for purchase.`;

}

if( room === Rooms.Auguary)

{

return `Unlocks the Augury powers for purchase by any Operative`;

}

// And so on

}

Finally, nothing after the return statement of a function is evaluated. In the above code, I have multiple return statements because I only ever want to return one value and then be done.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

function myFunc(value) {

value = value + 5;

return value;

value = value -1; // Note executed

return 30; // Not executed.

}

Anything below a return statement is considered “dead code” and should be removed.

Modifying variables with functions

Functions do not modify the variables they are passed in!

What do you expect this code to print at points A, B, and C?

Run it and see if you were right.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

function incrementNum(num) {

num = num + 1;

return; // Note this doesn't return anything

}

let x = 10;

incrementNum(x);

console.log(x); // Point A

let num = 20;

incrementNum(num);

console.log(num); // point B

num = incrementNum(num);

console.log(num); // Point C

Were you right?

*

*

*

*

*

* Answers below

*

*

*

*

*

Point A prints 10

Point B prints 20

and Point C prints “undefined”

There are two takeaways here: the first is that functions operate on copies of the variables they are passed in. It doesn’t matter what the variables are named when you call the function, it makes a copy. If you don’t return that copy, the outer code has no way of knowing what went on inside the function.

The second takeaway is that you have to return something. If you don’t, you will get undefined.

Let’s look at one more example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

function myFunc(num) {

num = num + 1;

return 55;

}

let y = 1

myFunc(y);

console.log(y); // Prints 1. y was never reassigned.

y = 20;

y = myFunc(y); // Y has a value of 55.

// Even though It was passed in as y, and its value was changed,

// the function returned 55. Each function only returns one thing. Everything else is lost.

Functions only return one thing. If you want to return multiple things from one function, don’t. Reevaluate your approach or use multiple functions. While it IS possible to return an array or object with multiple values, you shouldn’t need to at this point, and are probably heading down a wrong path.

If and Equality

Conditionals check if something is true or false. We can set a variable to these values directly (let finished = false;), and check their value (or update them) later. We can also perform a check to get a conditional (or “boolean”) value: let isRich = money > 1000000);. Both of these would have a value of false.

But booleans are only useful if we can check them, and change our behavior as a result. That’s where conditionals come in!

If: Checking Conditions

Sometimes you only want to do things conditionally. Check the players strength. If it’s greater than 10, deal 1 extra damage.

Ignoring the parts where we actually get the players strength or set the outgoing damage (we’ll talk about both next session ), here’s how a conditional might look:

1

2

3

if(strength > 10) {

damage = damage + 1;

}

The if statement is created by the word “if” followed by parentheses (()). Inside the parentheses is your condition, the thing you’re checking. Usually this is comparing two variables, like with greater than (>), less than (<), greater than or equal to (>=) or less than or equal to (>=). We’ll talk about equality in a moment.

Then you have curly brackets {}, and the body of your if goes in between. Unlike a function, you won’t return anything, and any variables you modify within the if will still be modified outside of it!

While you can modify existing variables inside your

ifstatement, do not create new variables there. Instead, create them before theifand modify them within, if necessary.You can always give them a default value (like -1 or

undefined) when declaring them, and then check if they have a “real” value later on.

Everything between the () of an if statement will be converted to a boolean value and deemed to be either true or false.

And that’s an if statement! They can also be combined with else statements for greater effect.

Danger: Do not mistake the

ifstatement for a function. It looks like one, but it is not one. Rather, it checks a condition and either executes the code within it, or it does not. Critically, unlike functions,ifstatements don’t return a value.

Else

We can check if something is true, and do something if it is. But what if it’s NOT true?

Sure, we could chain ifs together:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let greeting = ""; // Default value

if(strength < 10) {

greeting = "You're scrawny!"

}

if(strength > 10) {

greeting = "Can I help you with anything?"

}

This works (well, almost. Note that if strength is exactly equal to 10, our taunt remains empty), but it’s not very clear. And we accidentally found a bug already! If our logic changes, we have to update both if statements.

Let’s try else instead!

It’s exactly what it sounds like. if(x) { do something} otherwise (else) { do something else }

The same code from above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let greeting = ""; // Default value

if(strength < 10) {

greeting = "You're scrawny!";

}

else {

greeting = "Can I help you with anything?";

}

We could also chain with else if:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

let greeting = ""; // Default value

if(strength < 10) {

greeting = "You're scrawny!";

}

else if(strength < 20) {

greeting = "I be you spend all your time lifting ROCKS!";

}

else {

greeting = "Can I help you with anything?";

}

Tip: Don’t put a

;semi-colon at the end of an if statement: these always need to be followed with curly braces ({}).

And and Or

And

What if you want to do something only if two conditions are true?

You can embed if statements:

1

2

3

4

5

if(height >= minHeight) {

if(x <= maxHeight) {

goOnRollerCoaster();

}

}

or you can AND two conditions together:

1

2

3

if(height >= minHeight && height <= maxHeight) {

goOnRollerCoaster();

}

Isn’t that better?

Note the DOUBLE AMPERSANDS (

&&). Using a single ampersand will not do what you want!

We can do a similar thing with OR:

Or

The naive way results in a lot of duplicated code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

if(hasReservation) {

SitAtTable();

OrderFood();

Eat();

}

if(paidBribe) {

SitAtTable();

OrderFood();

Eat();

}

Let’s use an Or! || double pipes is the tool we need:

1

2

3

4

5

if(hasReservation || paidBribe) {

SitAtTable();

OrderFood();

Eat();

}

There’s more to this topic, like the concept of “short-circuiting”, where part of your evaluation may not be checked, but for your needs, this should be sufficient.

Equality

What if I want to check if two things are equal?

Easy, just use ===:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

function isCorrectPassword(guess) {

if (guess === "open sesame"){

return true;

}

else {

return false;

}

}

if(isCorrectPassword("Syzygy")) {

openSecretDoor();

}

Or, to check if the values are different, use !==

1

2

3

if(guess !== password){

console.log("Try again!");

}

In JavaScript, as with many programming languages, the

!symbol means “not”. CSS is an outlier, using!importantto mean “very important”

Why three Equals?

One equal sign is used for assignment (let name = "Alex"), so why do I need THREE equals for comparison?

That’s a fair question, and the answer is you don’t, not really. But you should anyway. I’ll explain.

We use = for assignment and multiple equals for comparison. This is to avoid confusion.

While it is possible to assign a value inside an

ifstatement, never do this. It will only lead to confusion.if(name = "alex")is assigning the value of “alex” to the name variable, and then will always return true. That is most likely not what you want(If you’re curious why it returns true, it’s due to how JavaScript converts things into booleans. Look up “truthiness” or “boolean coercion JavaScript” for more details.)

You can use two equal signs for comparison, but this does loose comparison:

if(5 == "5") returns true, while if(5 === "5") returns false.

Being careful about types will serve you better in the long run, though I’ll warn you now: as you’ll see in the next section, Roll20 returns a lot of numeric values as strings (5 would be returned as “5” in some situations), so you’ll need to be vigilant about calling parseInt() to convert from string to number, or use == everywhere.

A specific example of why converting is better is that otherwise you WILL get unexpected results. 2 + 2 is 4, but 2 + "2" is “22”. You can verify this in your console for yourself right now.

If you intend to proceed further with web development, I strongly recommend using === and parseInt(), but if you choose to go forth with == alone, you do so with my warning, and at your own risk.

Loops

You may want to do things multiple times in a row, until a given condition is true.

There are two main types of loop in JavaScript, while and for. I’ll cover while first, since it’s much easier to comprehend.

A while loop looks like an if statement, except that the body of the loop continues to execute until the condition becomes false.

Make sure you have a way to exit your loop! If you set up an infinite loop, your browser will freeze and you will have to re-open the window (or, for some browsers, the entire application!)

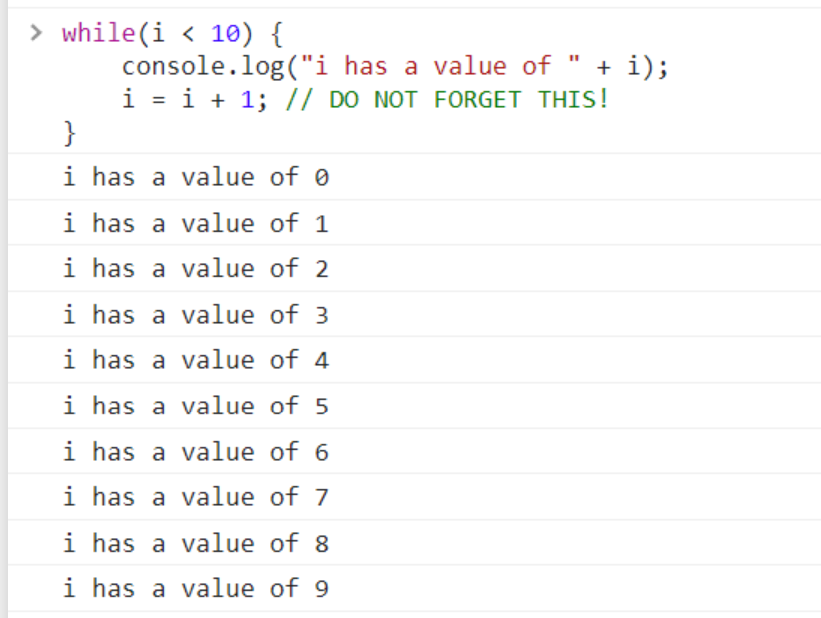

A while statement might look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

let i = 0; // Customary to use i as an index counter. Can use anything

while(i < 10) {

console.log("i has a value of " + i);

i = i + 1; // DO NOT FORGET THIS!

}

Note that there’s no ; before the {. Just like an if statement or a function declaration, lines of Javascript that open bodies don’t end with semi-colons.

This loop executes 10 times printing the values 0 through 9.

This loop executes 10 times printing the values 0 through 9.

tip: If you need to increment a value, instead of

i = i + 1, you can usei++.

A for loop has syntax that can be a bit overwhelming, but is extremely commonly used. You can always write a for loop as a while loop instead, if that makes you more comfortable.

A for loop looks like this:

1

2

3

for(let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(i);

}

Woah, let’s break that down!

let i = 0; (note the ;). This is our declaration.

i < 10; (again a ;). This is our condition to end.

i++ (No semicolon!). This is our increment, it happens every loop.

A for loop performs the declaration (or initialization) once, before the first pass. It then performs the condition check (and again at the start of every loop). Then it does the items within the body of the loop, and finally, as a last step, it does the increment.

For loops are the most common in “real” code, and I will use them when dealing with repeating sessions. You can copy/paste as needed. I may give one example in a while loop as well.

Listeners

Certain actions create events. Events are created from actions like clicking on an element, changing a dropdown, or editing a textbox.

Roll20 lets sheet creators provide special functions that can listen for these events and react to them. These are called listeners.

A listener is a function that takes in one argument. That argument (or parameter) includes all of the information you need about the event that triggered it. If a listener fires due to an input being changed, the parameter will include both the old value and the new value.

A listener has two parts: the event it’s responding to (like “when HP changes”) and the code it should execute.

You can have one listener react to multiple different events. For example, a weapon in cyberrats has three range checkboxes, one for Close, onr for Near, and one for Far. If any of those checkboxes are clicked, I call the same function, which updates the text of the weapon’s range.

Beware! If you update the value of an attribute from within a listener, that change may trigger a different listener. It’s possible to get into an infinite loop. If you’re changing a value that has a listener on it, you may need to disable events first.

A listener looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

// Reset after each mission

on("clicked:reset", function() {

// Respond to the reset button being clicked

}

); // Close "on"

Note: “reset” corresponds to an action button with the name “act_reset”. We also ignore “act_” or “attr_” in our listeners.

This is a button click, so there’s no “changed” information. Note that on() is a function that takes two arguments: the first is a string that says what we’re listening to (in this case “clicked:reset”), and a function that says what we should do. This function doesn’t have a name. Notice on line 5 of the coe above, we have );, which closes the on() function. The } on line 4 closes the nameless (or “anonymous” function we start on line 2.

A full example of a change listener looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

on("change:smash", function(eventInfo) {

const newVal = parseInt(eventInfo.newValue); // Parse to differentiate between 5 and "5"

const roll_formula_smash = buildDicePool(newVal);

const roll_results_smash = getResults(newVal);

setAttrs({

roll_formula_smash,

roll_results_smash,

});

});

This looks very similar to the last, except that our anonymous function on line 1 has a parameter, which I’ve called “eventInfo”. It’s a good idea to console.log(); this parameter, both to verify that your listener is firing, and to see what values are being passed in.

On line 2 I parse the newValue property from a string to an int. Roll20 gives all inputs attributes as strings, so it’s important to parse them to integers with parseInt() if you want to do math with them (see also we we use ===, above).

Line 4 and 5 I call functions to get values based on my input (in this case calculating Roll20 dice strings), and then in lines 7-10 I set variables using those values with the built-in setAttrs function. This is a very common pattern you will use yourself.

We’ll talk more about listeners in the next session.

Bonus: Refactoring

This is a bit of an advanced topic. I recommend you write code, bad code, terrible code, code that works, before you ever give a thought to making it better, cleaner, or easier to use. Perfect is the enemy of good.

If you are embarrassed by code you wrote six months ago, you’re growing.

The code I’m writing here is meant to be easy to read. The code you right will probably be the same. But the more code you write, the less verbose your code may grow.

Let’s look at an example from earlier this session:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

function isCorrectPassword(guess) {

if (guess === "open sesame"){

return true;

}

else {

return false;

}

}

There’s a few ways we could clean this up. First, we don’t need the else. Nothing after a return statement is executed, so we can simple have this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

function isCorrectPassword(guess) {

if (guess === "open sesame"){

return true;

}

return false; // Not reached if the condition was true!

}

Second, we don’t need to explicitly return true or false, we can just return the result of our check directly.

1

2

3

function isCorrectPassword(guess) {

return guess === "open sesame";

}

Finally, a minor quibble, we probably don’t want to reject “Open Sesame”, so let’s ignore the case:

1

2

3

function isCorrectPassword(guess) {

return guess.toLowerCase() === "open sesame";

}

toLowerCase() is a built-in function that all strings can call. Note that it doesn’t MODIFY the string, it returns a new string:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

let name = "Alex";

name.toLowerCase();

console.log(name); // Still "Alex"

let lowerName = name.toLowerCase();

console.log(name); // "Alex"

console.log(lowerName); "alex"

Summary

Congratulations! You know the very basics of JavaScript, and are ready to move on to the next session where we will apply those basics in the context of Roll20.