I talk to Asa Donald about destroying character sheets, the role of music in RPGs, and channeling real-life burnout into mech games.

Transcript adapted from an interview with Asa Donald on May 8th 2025.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length

Alex: You recently released Rust No More, your solo mech game with blackjack mechanics. Can you talk about that game?

Asa: One quick correction, it’s Rust Never Sleeps.

Alex: Golly, I feel the fool!

Asa: I think you were conflating Sleep No More with Rust Never Sleeps, right? That’s funny, I’ve been thinking about Sleep No More a lot recently.

Alex: Forgive me.

Asa: So Rust Never Sleeps is a grunge solo RPG about doomed mech pilots. Basically, you’re this mech pilot, and you’re fighting a hopeless war against an authoritarian, and you’re doomed to burn out at some point in time. You have a deck of cards, and it’s your mech’s battery pack. And every time you use your equipment, you’re using up those cards, you’re taking one step closer to burning out. So you’re going on missions, and every time you go on a mission, you’re just trying to finish that mission without running out of cards. But the way that the game works is after every mission, you also have to remove a card. And that inevitably, you know, leads you to running out of your battery.

And eventually, you will burn out. You are doomed to burn out in the process.

Alex: It seems like you were intentionally trying to mechanize this process of burning out, of being doomed from the start. It reminds me of The Wretched by Chris Bissette.

Asa: It’s very intentional, that process. There’s actually a lot of mechanics that relate to burning out. I don’t want to get into them because I want people to think about them and sort of explore how the mechanics tie into the themes here. But there are a lot of mechanics related to pushing your luck in the game and there’s sort of like…

One of the reasons why I wanted to stick with blackjack as a resolution mechanic is that you reach these really interesting points where you are like right on the edge of success and you can either choose, you know, “Am I gonna push it for success, or am I gonna face a potential consequence here for failing?” If it’s going to affect the story in a certain way there’s got to be a mechanical consequence.

Alex: That totally makes sense.

Asa: You don’t always know when it’s happening, but you’re faced with this question of “All right, do I push it for success, knowing that if I fail, then I’m going to suffer a larger consequence?” There are meant to be a couple of different types of mechanics around pushing your luck — One of them is instead of just doing like a basic skill check, what you’re really doing is like a skill challenge where you need a certain number of successes but if you hit a certain number of failures first you actually fail whatever you’re trying to do.

Another one is the challenge, where the idea is that you’re eventually going to succeed, but the question is how efficiently you succeed. In that case, the question becomes is it worth it to push your luck in the hopes of getting an extra success, some extra bonus? At every step, the game is encouraging you to push your luck and take you one step closer to burning out.

Alex: I like that interplay of mechanics and themes.

Asa: I’m really interested in burnout, both thematically — like the name “Rust Never Sleeps” comes from Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps, but it’s also lyrics, and two of his songs on that album are very influential for the grunge genre. So I’m really thinking about burnout culture and the grunge genre. There are a lot of famous musicians in there who inevitably burn out and have really tragic backstories, and I’m thinking a lot about that in our modern burnout culture, how we ourselves are sort of pushing ourselves for that success. You know we’re on the brink, are we going to keep pushing ourselves? I think there may be some sad meaning behind it as well, like when burnout feels inevitable in the game, well, that’s something I’m thinking about with real life as well. I may have rambled a bit there.

Alex: No, you actually pre-empted a few of my questions. I’ll circle back to a few of these, but first, you mentioned the skills challenge where you have a number of successes and failures. Is that something that, I mean, I was first introduced to that with Dungeons and Dragons fourth edition. Is that an inspiration, design–wise for you?

Asa: Yeah, it was in some ways, but, really it’s a larger sort of OSR tradition that has explored those types of things. I’ve written a couple of OSR—style games, and skill challenge–like things are a part of it. Really, I’m trying to smooth out some of the mechanics a little bit. In some of the adventures I was writing, I was exploring this because I wanted them to be things that people could play together or play solo. Even with this game, something I’m thinking about is expanding it out for a duet style game, or a multiplayer game. I think I left myself some cool opportunities with the set up.

To answer your question, what I like about skill challenges is the same thing a lot of people like — there’s a lot of dramatic potential. They encourage people to think about narrative and to think about story and be more inventive. It’s one of those moments where you’re giving that narrative authority to the players instead of the GM.

I find it really cool how solo games have this unique flexibility, and I want to explore that. For me, these [skill challenges] are a really cool way for me to make it work within blackjack. Not just “I’m going to push it on this skill”, but suddenly, “I’m going to push it because I want the scene to succeed, I want to accomplish this much larger challenge or obstacle.”

Alex: You want the players to be thinking about the story, not the game. When did Rust Never Sleeps begin?

Asa: It was mid-December, I was working on fulfilling this crowdfunder that I had done—

Alex: That’s a fast turnaround for you, starting in December!

Asa: Yeah, it was fast. I mean, this is the beta that I’ve released, that’s how I’m viewing it right now. I’m trying to approach this in a very different way than my other games.

Alex: Sure.

Asa: The idea struck me in December, where I started thinking about that card pack, and how a card pack could basically be a clock, in the same way that HP is in some ways a clock. Thinking about, “Okay, here’s this limited resource that we have”. And what I love about the card deck is you can see it shrink, shrink, shrink. I was trying to find different ways of making it into a game, and I was listening to an Audiobook — I love audiobooks, this was the great Iron Widow, it’s mecha related, I highly recommend it — and it just clicked. I was just thinking like, “Oh, that would fit perfectly!” and then all of a sudden I started thinking about all of these things that I wanted to do with it, and I’m like, “I have to write this game.”

I actually sat down and in about two or three weeks, I had basically written up a very rough first draft. I was like, wow, I actually think I really have something cool here! And especially with that character sheet that I’ve been working on—

Alex: Yes! I want to talk about that more. I love that character sheet!

Asa: I honestly think that’s what, you know, what ends up hooking a lot of people. You had a great pull quote which I use for the game, “This may be the coolest character sheet I’ve ever seen,” and I’ve actually had a couple other people say similar things—

Alex: I stand by that! It hooked me the moment I saw it.

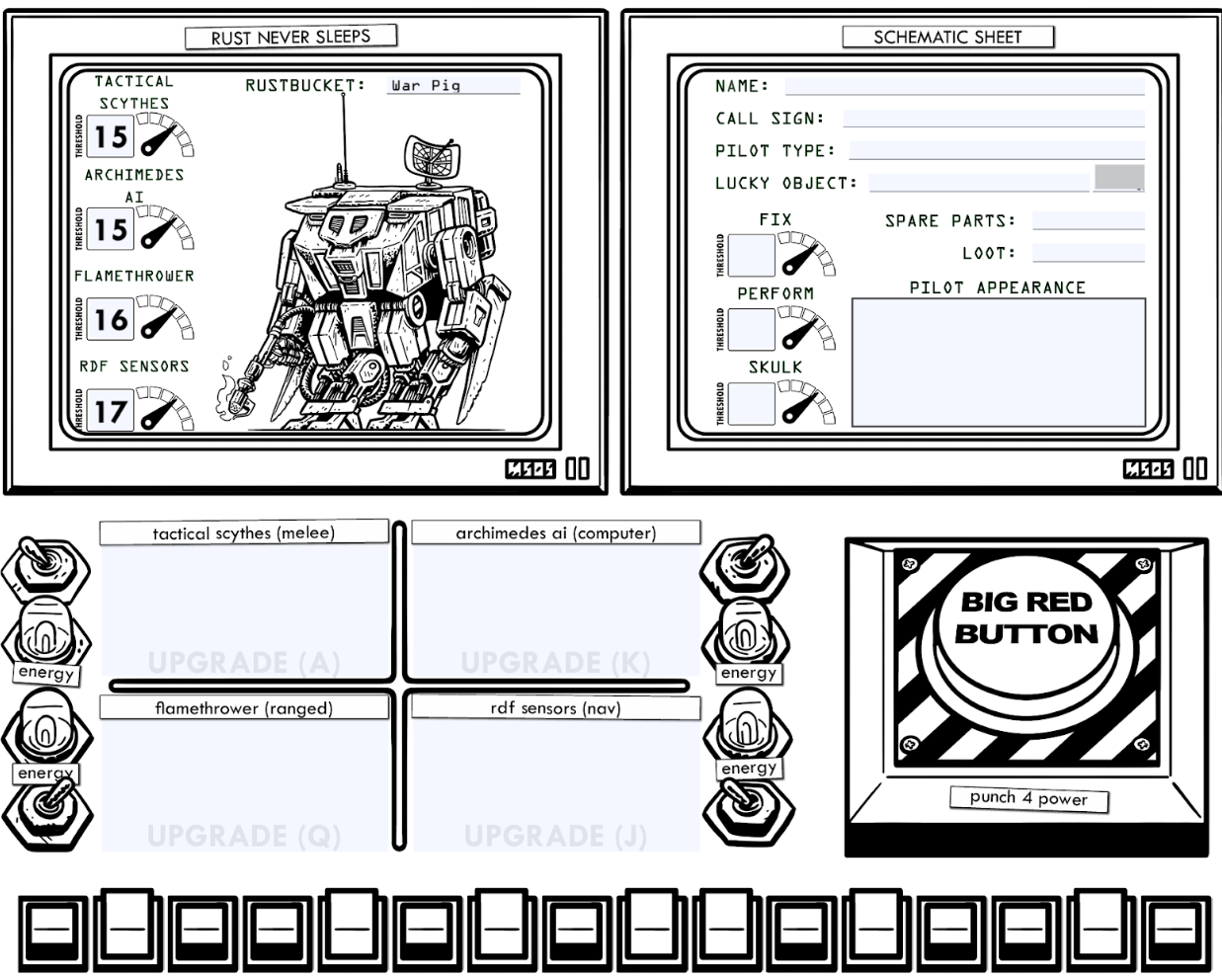

The Rust Never Sleeps character sheet has you drawing wires and coloring in bright bulbs.

The Rust Never Sleeps character sheet has you drawing wires and coloring in bright bulbs.

Asa: What I was looking for in that character sheet (or as I call it in this case, a schematic sheet, because it’s not just about your character it’s also about your mech), the first thing I wanted when I was thinking about this is I wanted a keepsake or an artifact of play. I wanted to be really visually appealing too, but there’s a reason why I wanted that keepsake.

I wanted there to be some physicality to it, with that keepsake. I wanted it to resemble an actual mech’s cockpit. The front page is meant to have two monitors on it, a bunch of toggles and things. It has lights and you’re meant to have to color in these lights as you end up upgrading your mech, and you have to color in your mech. On the sheet on the back side there’s a hole that goes into your dashboard and you reach in and you’re connecting wires basically to your battery pack, and the way that you connect those wires is by drawing with coloring utensils on them. Those are all connected to different suits that you’re drawing from your deck. So you’ll color a red wire and connect it to a certain part to signify this upgrade. I think those are the really cool things I want players to interact with. Not just coloring wires, but all of it. One of the things I love is like you know somebody’s about to lose, right, and this is that push your luck mechanic: here it looks like you’re gonna fail and then somebody slams this big button.

Alex: Yes! The big red button!

Asa: So I label the big red button on the character sheet, and the idea is you’re supposed to slap it sort of like in slapjack or when you say, “Hit me” in blackjack. So I want people

to really engage with that sheet in a bunch of different ways.

But the real reason I wanted a keepsake is because I wanted players to treasure that character sheet, and then afterwards I wanted them to destroy it. I think it’s really cool to have a keepsake, I think it’s really cool to destroy stuff. But when you combine those two, I think that there is like this moment of catharsis that it can really create an idea in the game. When your rust bucket burns out, you burn your character sheet as well.

Alex: I could talk about this character sheet all day, but I want to keep moving because there are a few more questions I want to ask. First, there’s some real historical drops here in this game. Rust Never Sleeps is firmly rooted in Washington state. What prompted that?

Asa: I’m really interested in writing about different regions of America, especially post-apocalyptic regions, thinking about a sort of American Gothic through the history of the US, and the way it colors our present in our future. I was talking to somebody who liked some of our other games, and they live in Washington, and were telling me about some of the weird and bizarre things around them. They told me about the WPPSS or “Whoops” nuclear plants and I wanted to incorporate that as part of the apocalyptic events.

And of course, a lot of the playlists are inspired by grunge, and I wanted to connect that to the Seattle scene [where grunge was born]. Throughout the missions, I try to work in some of those small regional things, sort of as Easter eggs for folks who might be from the Washington area. I also really like planting things within a real space. For me, that helps me write, but I also think it helps ground people in the fiction as well.

Alex: You mentioned it before, but it seems like music has been a huge source of inspiration here. Can you say more about that?

Asa: Yeah, but I might go on too long! (Laughs). Music to me is really interesting in games. I think that we often do not — we’re too busy enjoying moments where we are playing games and there might be music in the background or musical themes or what have you, where we might be enjoying the music, but we’re not appreciating some of the things that it’s doing. And I think on a very basic level that what people are doing with music, they’re, you know, using it to set the mood right they’re using it to incorporate themes.

Alex: Music is really good at reinforcing the magic circle.

Asa: I love it, for example, you’re watching film or TV shows, and there’s a cool moment where it pulls you a bit out of the narrative. I feel like when you hear this music and it’s very thematic, or there might be irony created through the music, which I love too. I find that really enhances play!

And then there’s a cool diegetic things too where you know music is playing for the character but it’s also music that we the audience are listening to and there’s some cool things going on there.

Alex: Like your mech’s cassette tape.

Asa: Yes! And the final thing which I love experimenting with, and I think a lot of people do is music isn’t always just there to contribute. It can also be taken away, and when you take away music and gameplay that to me is even cooler like that silence that suddenly exists… when it’s done right, that can be really powerful for people. Just like in Ten Candles, which I’ve been thinking about recently from the great Dice Exploder interview with Jay Dragon about how when you take away that light, it’s sort of setting the scene, sort of like descending into a movie theater in some ways, as sort of this ritual moment. Things like turning off music has that impact as well.

Alex: One of my favorite musical experiences is the moment of silence Alanis [Morissette] hits us with in All I Really Want. Here, can you handle this?

Asa: I think a lot of us use music for inspiration, but I’m interested in exploring a bit more beyond inspiration, looking at how we can use music in play, and how it can be incorporated into mechanics. Void 1680 is a prime example, a behemoth in the indie scene. Avery Alder’s Ribbon Drive is so incredibly cool, and not celebrated enough. It’s a modest book, but there’s so much cool stuff that it does so casually that hasn’t been reproduced anywhere else.

Alex: Can you say more about the kinds of mechanics you’re interested in with music?

Asa: [Avery Alder] doesn’t use the language, but the playlists, the music is used the way an oracle would be used in GM-less games, in some ways. But this is multiplayer games, where the music is used for inspiration to create scenes and inspire moods. Usually you’re listening to music in silence until someone enters the scene, and there’s a cool moment because it’s based on a road trip where, again, you get some of those diegetic elements that I love.

I’m building something similar for Rust Never Sleeps, these mission generators. I was working on them, but they just weren’t quite clicking until I realized you can use music as an oracle, in a similar way like shuffling a playlist isn’t so different than shuffling a deck of cards and drawing one out.

In Ribbon Drive, it feels so natural, but I think you’re asking a lot of players to say “Listen to this music, and start using that to imagine a scene.” So I created some scaffolding, which I called the Grunge Bank, where you get an opening theme to your mission, which might be chosen for you. And you can use that to identify the themes of your mission, whether that’s coming from evocative words and terms, or elsewhere in the music. And you’re going to actually bring those into the game at some point when you need inspiration, or when you need to describe a character.

Alex: There’s definitely some untapped potential there, and I can tell music is a passion of yours, but I’m going to switch gears. How would you describe yourself as a creator? What makes an Asa Donald game?

Asa: Growth. Honestly, I feel like it’s about growth. That’s what makes me a creator. You know, I think it’s the reality for a lot of people. We [as an audience] know you as a creator, and we only have that limited relationship. We don’t always see how people are growing, growing, growing.

There’s this progressive fallacy where your next work is always better, always better. And again, it is a fallacy, but for me that’s a real thing. I feel that every time I’m working on something I’m gaining new skills, and I know that’s true for a lot of designers. For me specifically, it used to be a lot about like, “I’ve got this cool idea I want to share it with people”, but more recently, it’s been, “I’ve got this cool idea I want to share with people, but I need to develop the idea more. I need to develop myself personally. So I might be creating content, but in the process, I’m also working to better understand different design principles and philosophies, different, you know, schools of design.

So, yeah, I’m really taking growth a lot more seriously than I used to. Growth can be excruciating! You know, I’ve done some cringe-worthy stuff as a designer too, but that’s how you grow. So I’d say that growth is sort of what defines me and my games.

Alex: It sounds like the “Content creation” is almost a byproduct of growth! (Laughs). Before I let you go, I want to come back to something you said earlier. You expressed an interest in expanding this game into a duet (or larger!) game. What are your experiences in these spaces?

Asa: I’m going to be brutally honest with you, Alex. I have absolutely no experience in the duet space! And so this too is part of my growth (and maybe a sign of my hubris)… What’s tempting me to grow in this direction is how appealing a duet mode of play is within the mech genre. I mentioned Iron Widow earlier, which depicts mechs that require two people to fly them, and I think of real life with pilots and co-pilots on our airplanes. And I think of Nevyn [Holmes]’s Mech&Pilot and Gun&Slinger games, which I’m hoping to play some time. So I say, Why not rustbuckets too!?

In fact, Aaron Lim (a really insightful designer, whom I admire) took a look at an early draft of RNS and pointed out how easily it could be adapted for multiplayer, and I started looking at the game differently after that. Beyond its grounding in the genre and, well, reality, I think duet play lends itself well to RNS as a GMless game, as well as a game in which you draw at least two cards for Blackjack-inspired resolution too.

There’s something very appealing to me about two players taking turns drawing from a shared deck and placing their cards with one another to form a Blackjack hand. That moment in which they create a hand together for resolution of an action is unifying. I also think it will easily fall into GMless multiplayer play (with separate decks and mechs), as one of its core components is based on skill challenges, which is a mechanic that interests me in how it invests more (or sometimes all) narrative authority into the players.

Of course, for me this is a solo game. I design its modules and materials with a solo-first mentality. I need to. But I think I said earlier that “play” in the indie ttrpg space is broader than we think. Play can mean experimenting or making a game your own, adapting it for your own circumstances and play style. There is actual pleasure and enjoyment in that, which is why there are so many of us ttrpg designers. For Rust Never Sleeps, the duet and multiplayer options are fertile ground for fruitful play, and I want to invite it. In fact, don’t forget that Rust Never Sleeps is still a beta. The beauty of the beta is that it is unfinished, and it asks the community to finish it.